Mount Baker was named by George Vancouver after his third lieutenant, who was the first on his ship to see it.

Although the name is better than a few others in the Pacific Northwest, being the first person to see a giant mountain isn’t a particularly notable claim to fame. Especially when you have to ignore not only tens of thousands of people who lived there but also the Spaniards who had gotten there the year prior.

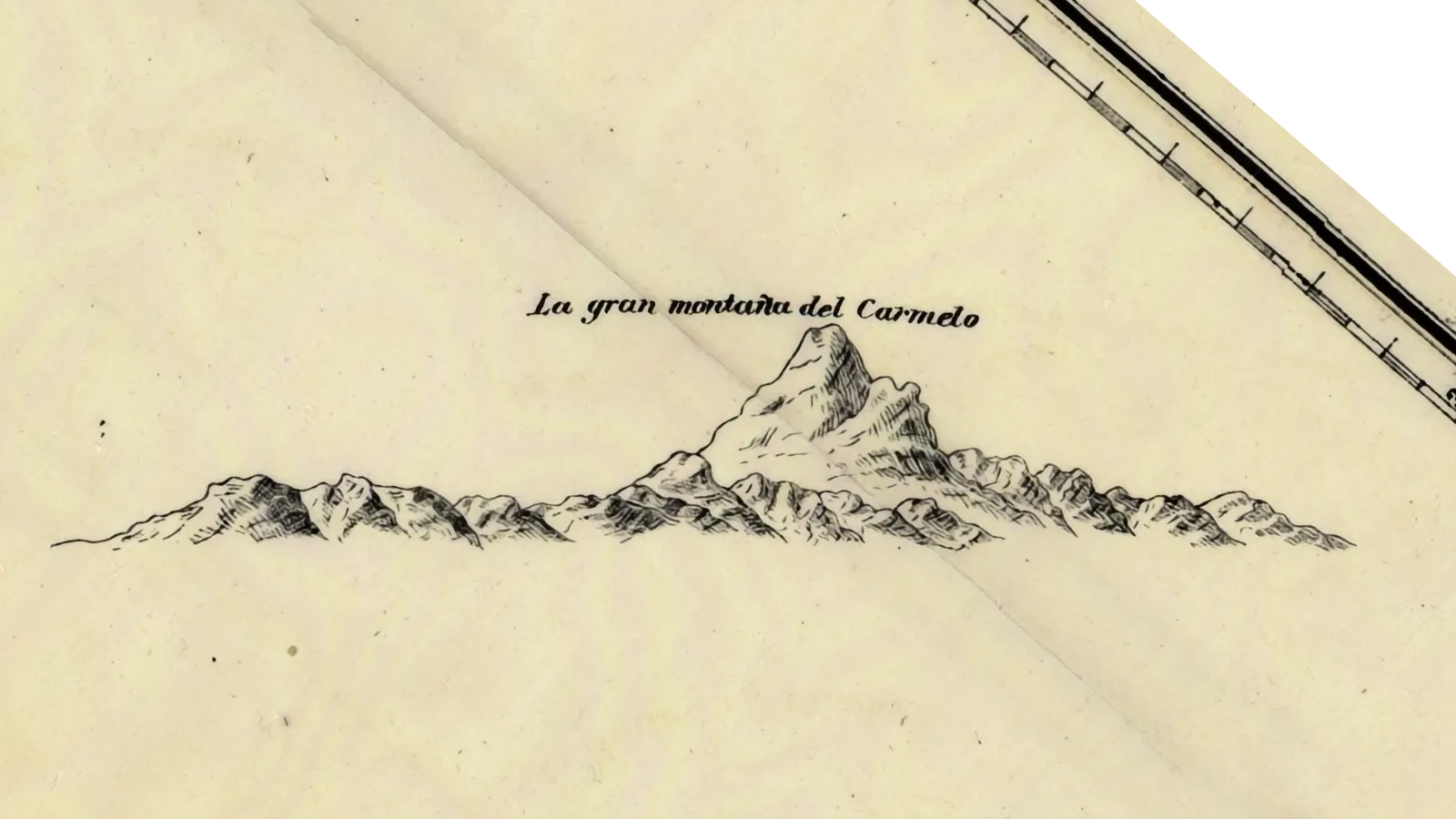

The mountain appears as la gran montaña del Carmelo on a map drawn by Gonzalo Lopez de Haro, first pilot on Manuel Quimper’s six-week expedition to the Juan de Fuca strait. The Spanish name is apparently a reference to a religious order whose white cloaks resembled the snow-capped peak. Who knows, if the Nootka Crisis had been resolved differently, it’s entirely possible that Europeans would have ended up calling it Monte Carmelo.

Instead, the name Mount Baker stuck after Vancouver described it in his published memoir.

About this time a very high conspicuous craggy mountain … presented itself, towering above the clouds: as low down as they allowed it to be visible it was covered with snow; and south of it, was a long ridge of very rugged snowy mountains, much less elevated, which seemed to stretch to a considerable distance … the high distant land formed, as already observed, like detached islands, amongst which the lofty mountain, discovered in the afternoon by the third lieutenant, and in compliment to him called by me Mount Baker, rose a very conspicuous object … apparently at a very remote distance.

George Vancouver

Vancouver’s diary mentions encounters with different indigenous groups of the area, some friendly and some indifferent,1 but he never stuck around in the same place long enough to learn their names or pick up their languages.2 If he had, he might have recognized Mount Baker by the name kwelshan, the term used by the Lhaq’temish (Lummi) people around Bellingham and the San Juan Islands, or swáʔləx̣, reportedly used by the nəxʷsƛ̕áy̕əm̕ (Klallam) people on the Olympic Peninsula.

The mountain itself is surrounded by the traditional lands of the Nooksack and Upper Skagit peoples. The Nooksack use kwelshán for the high open slopes of the mountain and kweq’ smánit for the glacier-covered summit.