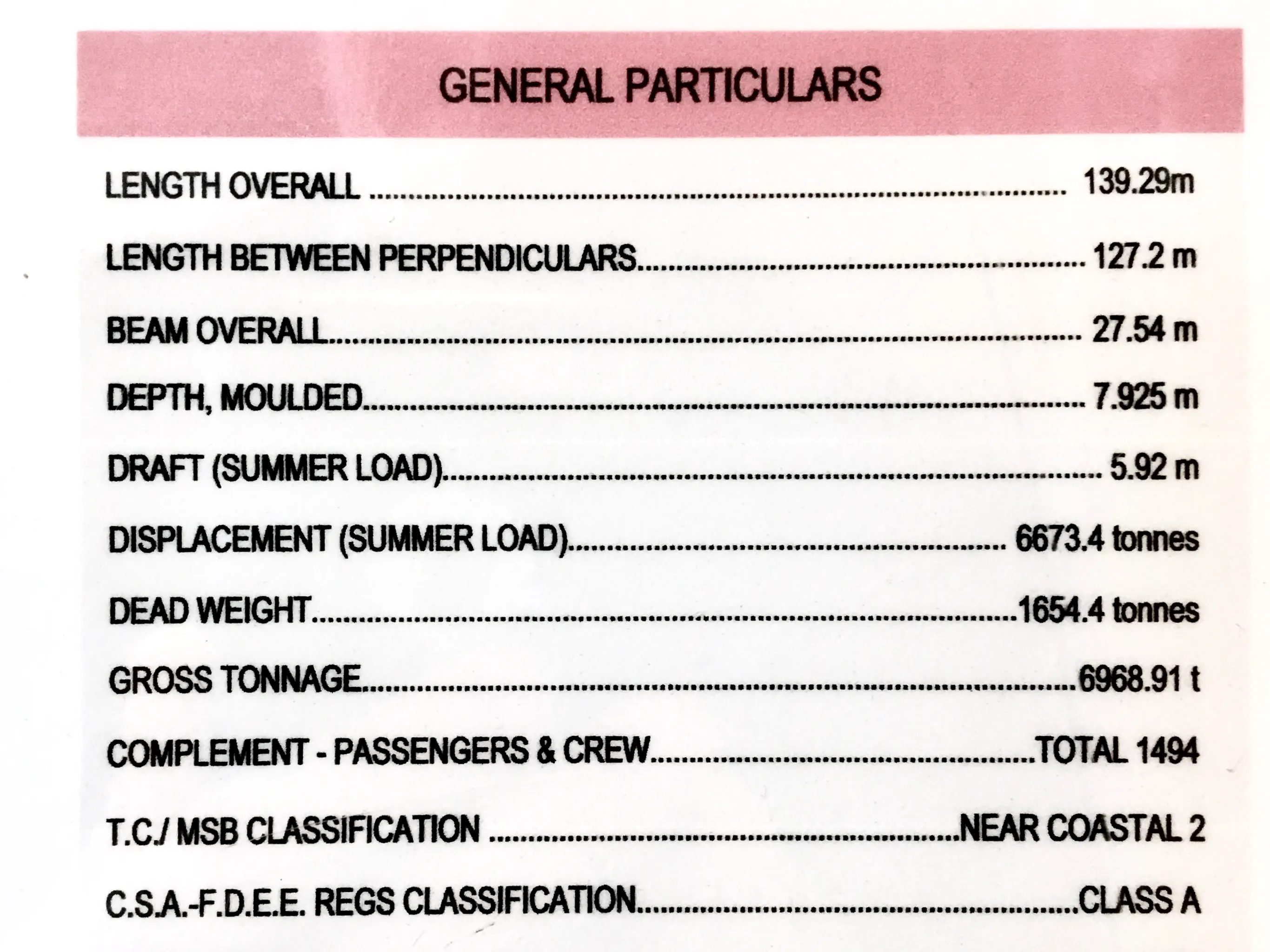

Ten years ago, I discovered that a disproportionate number of posts on Twitter had exactly 140 characters. Five years ago, I found the spike had shifted to the new 280-character limit. Now, Twitter has imploded and lots of people have migrated to Bluesky — what does the post length distribution look like on the new platform?

Length distribution of two million 2024 Bluesky posts, fit to an exponential curve.

Once again, we reproduce the spike approaching the character limit, with 300-character posts accounting for over half a percent of the entire dataset — more common than any other length greater than 50.

Once again, we also see the effects of bots: two bots are responsible for posting random strings of length 46 and 256 every few seconds, causing those lengths to be overrepresented.

But this might be my favourite of the charts I’ve made in this series. Take a close look at the 140 and 280 character marks: a larger-than-expected number of posts are exactly those lengths or slightly shorter. The curve abruptly reverts to its original course — an exponential decay curve — immediately after those milestones. That’s exactly the behaviour we expect (and observe!) when people compose posts that are a bit too long, then edit them down to fit within a character cap.

It’s entirely possible that these might be the exact same spikes we saw in my last two charts in this series, if people are reposting their old tweets from yesteryear on Bluesky. But I suspect this is more likely evidence of people crafting messages to be cross-posted to multiple platforms, in which case they may be using tools that recommend smaller limits than those supported by Bluesky. Time will tell what hypothesis is right!