-

-

Continuing a decades-old tradition of mine, I present to you a collection of unusual signs, scenes, and objects in Japan that made me think: “gee, that’s random.”

Famously, everything in Japan has a mascot. I could have dedicated an entire post to cataloguing mascots, from Ishikawa Prefecture’s (石川県) mustachioed Hyakuman-san (ひゃくまんさん) to Pipo-kun (ピポくん) of the Tōkyō Police. But the mascot that made me do the largest double-take was that of the underground shopping mall Yaechika (ヤエチカ), which is represented by… a chibi version of the Dutch merchant Jan Joosten van Lodensteijn.

Jan Joosten says “Let’s collect stamps!” from the various shops in the mall.

Gashapon (ガシャポン) — capsule toy vending machines — are another staple of the Japanese commercial experience. The vast majority of gashapon sell figurines based on popular anime, manga, and game characters, but there is a long tail of products for niche interests. I myself got a light-up ornament representing the Fukutoshin Line from a Tōkyō Metro branded blind box.

Niche gashapon toys: bags for green onions, figurines from the children’s book Pan-dorobō, and a metro-themed ornament.

Japan is frequently described as a place where tradition meets modernity, where the old coexists with the new. That cliché is certainly true, but it doesn’t capture the full range of temporal incongruities about the country:

- Japan’s train system is decades ahead of us in terms of speed and convenience — but many of the actual trains are almost twenty years old and run on sixty-year old tracks.

- Paying with cash is much more common than it is in Canada — but so is paying with one of a wide variety of mobile payment options.

- Japan is near the top of the list of mobile phones per capita — but you can also find honest-to-goodness pay phones still operating in the wild:

Although pay phones still apparently exist in Canada, they’re less rare in Japan.

I was determined on this trip to eat yaki-imo (焼き芋), i.e. a plain roasted sweet potato. I can report that it is a very satisfying snack! There are plenty of other sweet potato flavoured treats at this time of year.1

A roasted sweet potato from a shop called Ms. Yakiimo.

Other commercial entries in the “Gee, that’s random” files include

- a face cloth of the Pokémon gym leader Larry folded in a way I found humorous,

- an ad for tap water,

- an extremely stressed-out penguin on the packaging for bath bombs, and

- a collection of stamps featuring historical figures, presumably for teachers?2

Some of my favourite pieces of Japanese media are the Katamari Damacy video games and their Shibuya-kei soundtracks. I didn’t find anything related to either on our trip — I didn’t expect to, considering they’re twenty-plus years old and were niche even in their time — but I did see a bunch of things that reminded me of the game. Case in point: this public art installation in Kanazawa,3 which looks all the world like a katamari.

The iron sculpture is Corpus Minor #1, by Janne Kristian Virkkunen. The weird character rolling a ball is the Prince, by Takahashi Keita.

Speaking of things that reminded me of Katamari Damacy, rows of water-filled plastic bottles were a common sight in Kyōto’s Gion (祇園) district. This is an apparently widespread, but ineffective, way to scare away stray cats.

There are many stray cats in Kyōto’s Maruyama Park, which nearby residents try in vain to ward off with water bottles.

Finally, I have a collection of statues that stuck out at me at a particular angle:

- A doofy dragon fountain at Fushimi Inari-taisha (伏見稲荷大社),

- A glowing maneki-neko (招き猫) in Narita Airport (成田国際空港),

- A statue of Maeda Toshiie (前田利家) with a tall gold-plated hat in Kanazawa (金沢市), and

- A statue of Godzilla in front of Tōhō headquarters.

Gee, that’s a random collection of statues!

-

I had Seven-Eleven’s sweet potato ice cream bar, which weren’t bad but fall short of my favourite red bean bars. As a side note, I can confirm that the excellent reputation of Japanese convenience stores is well-deserved; we made frequent use of Family Mart and Seven-Eleven. The latter is so successful that it has its own bank and took over the American 7-Eleven, which is now a fully-owned subsidiary of the Japanese chain.

-

I recognize eleven of the twenty historical figures: Matthew Perry, Oda Nobunaga, Tokugawa Ieyasu, Isaac Newton, Thomas Edison, Albert Einstein, James Watt, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Johann Sebastian Bach, Ludwig van Beethoven, and Murasaki Shikibu.

Many of their exclamations are puns — for example, Commodore Perry says “Perry good”, Newton and Edison have bilingual puns involving an apple and an electric light, and Einstein has a furigana pun indicating that the equation actually stands for a phrase meaning “extremely good”.

Originally, I had confused Bach for Gottfried Leibniz, since they had similar faces and Bach’s pun referencing “Air on the G String” would also work in Japanese as a pun on “area under a curve”. Leibniz, however, had a much poofier wig and would not be filed under “musicians”.

-

Kanazawa is home to the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art and has a few related installations around the city.

-

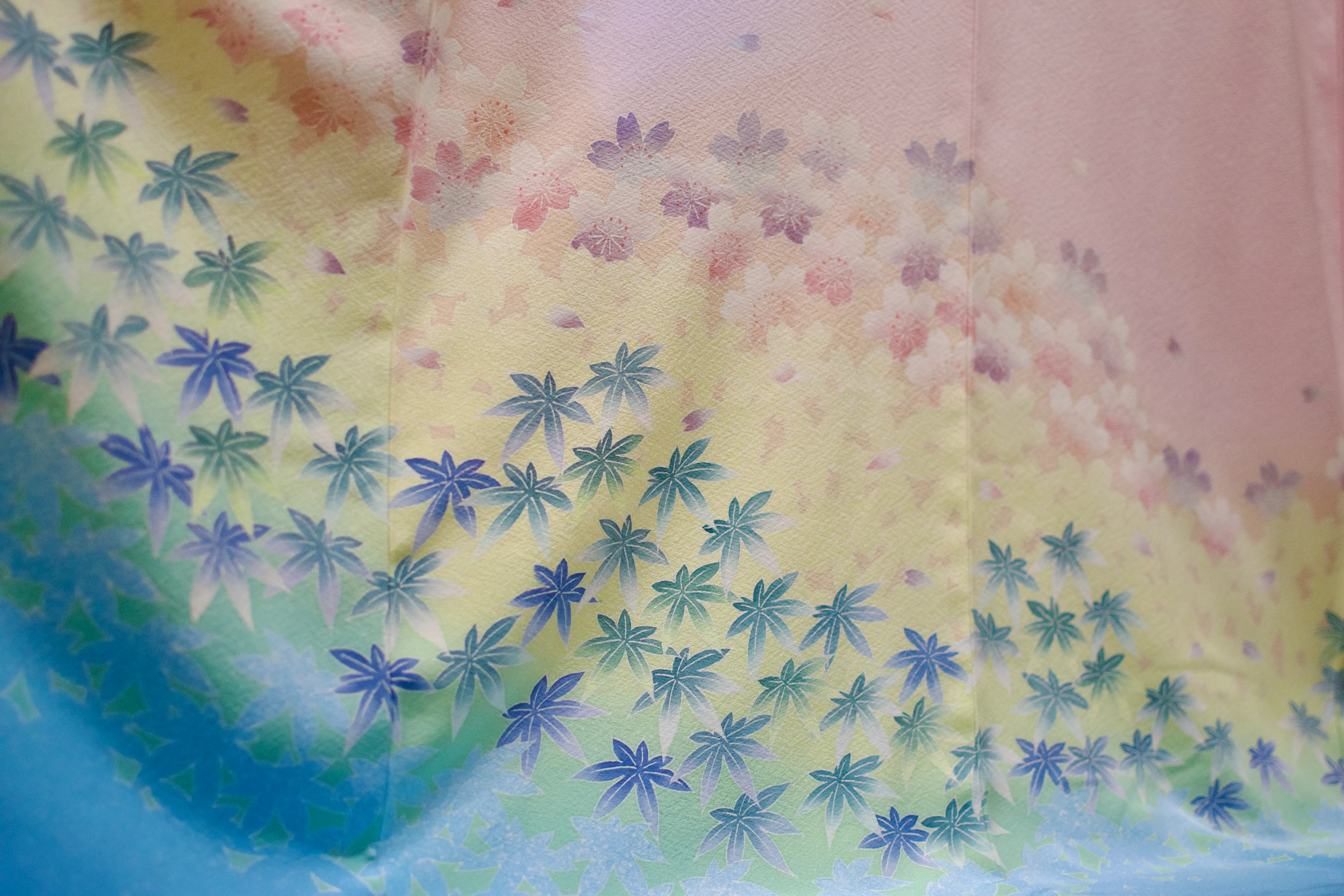

Yūzen (友禅) is a kimono dyeing technique that involves painting a pattern on the fabric inside the outlines drawn with a resist paste to prevent the dye areas from mixing together. In Kanazawa, we had the opportunity to learn and practice yūzen with the kind help of artist Hirano Toshiaki (平野利明) at the Yuzen Yomei studio.

Kaga yūzen — the style of yūzen unique to the historic province of Kaga — is characterized by lifelike designs such as insect-nibbled leaves.

Examples of yūzen displayed at the Kaga Yuzen Kimono Center.

Although less time-consuming than earlier freehand techniques, yūzen is still a skill-intensive multi-step process. Thankfully, the artisans at Yūzen Yomei made things easy for us by creating and outlining the designs ahead of time, so we only needed to worry about the colouring process.

We are incredibly grateful to Hirano-sensei for welcoming us into the studio. It was a very special experience — the highlight of the entire trip — and I hope to one day return to see them again!

We were honoured to contribute to a large collaboration piece for a local hospital.

-

Every day at five o’clock in the evening, many cities in Japan perform a test of their emergency broadcast systems. To avoid alarming or annoying their residents, the test consists of a pleasant melody to mark the end of the day.

Here are the melodies from Tōkyō and Kanazawa as I recorded them.

In Chiyoda, Tōkyō, the melody is the children’s song “Yūyake Koyake” (夕焼小焼)

In Kanazawa, the melody is the Westminister Quarters.

-

Tōkyō -

I visited the Ochanomizu Origami Kaikan (お茶の水おりがみ会館) as a fun little diversion in Tōkyō. The centre is part shop, part school, and part studio. I got to take some photos of the paper-dying process and took home some supplies that might inspire me to make some more origami soon!

Paper is dyed a solid colour and then flattened and compressed.

Origami paper can be dyed, painted, or both depending on the intended pattern. When I visited, the artisan was using a special multi-headed brush to paint green stripes on one side of the paper; the other side had already been painted gold using a very wide, soft brush to achieve a consistent finish. The result is a pattern perfect for folding into snake decorations for the upcoming new year!

The tools, process, and results of making origami paper.

-

As you might have guessed from an earlier post, I have acquired a minor obsession with the colours of fire hydrants. You can bet I had my eyes peeled in Japan to see how hydrants look there — and the answer was fascinating!

The first things I noticed in Tōkyō were the round red signs everywhere indicating the presence of a fire hydrant (消火栓)… and a distinct lack of fire hydrants.

It turns out that hydrants in Japan are generally installed underground except in particularly snow-prone areas. The signs point to the plate on the road or sidewalk that covers the hydrant cap.

Fire hydrant and fire cistern covers in Tōkyō, Kanazawa, and Kyōto.

Many parks and private property also have fire cisterns (防火水槽) and other water conservancies (消防水利) that store water to fight fires after a major earthquake, when the main water network may be damaged.

Water conservancies for fire prevention in Tōkyō.

Hoses, pumps, and other fire suppression equipment are scattered throughout the city so that trained residents and disaster volunteers can use them to suppress fires during a major disaster.1

A fire extinguisher tucked in the corner of Yasaka Shrine (八坂神社).

-

Apparently Vancouver has its own neighbourhood volunteer program in its disaster response plans, although it’s not clear whether it’s still active. I’d love to hear more!

-

-

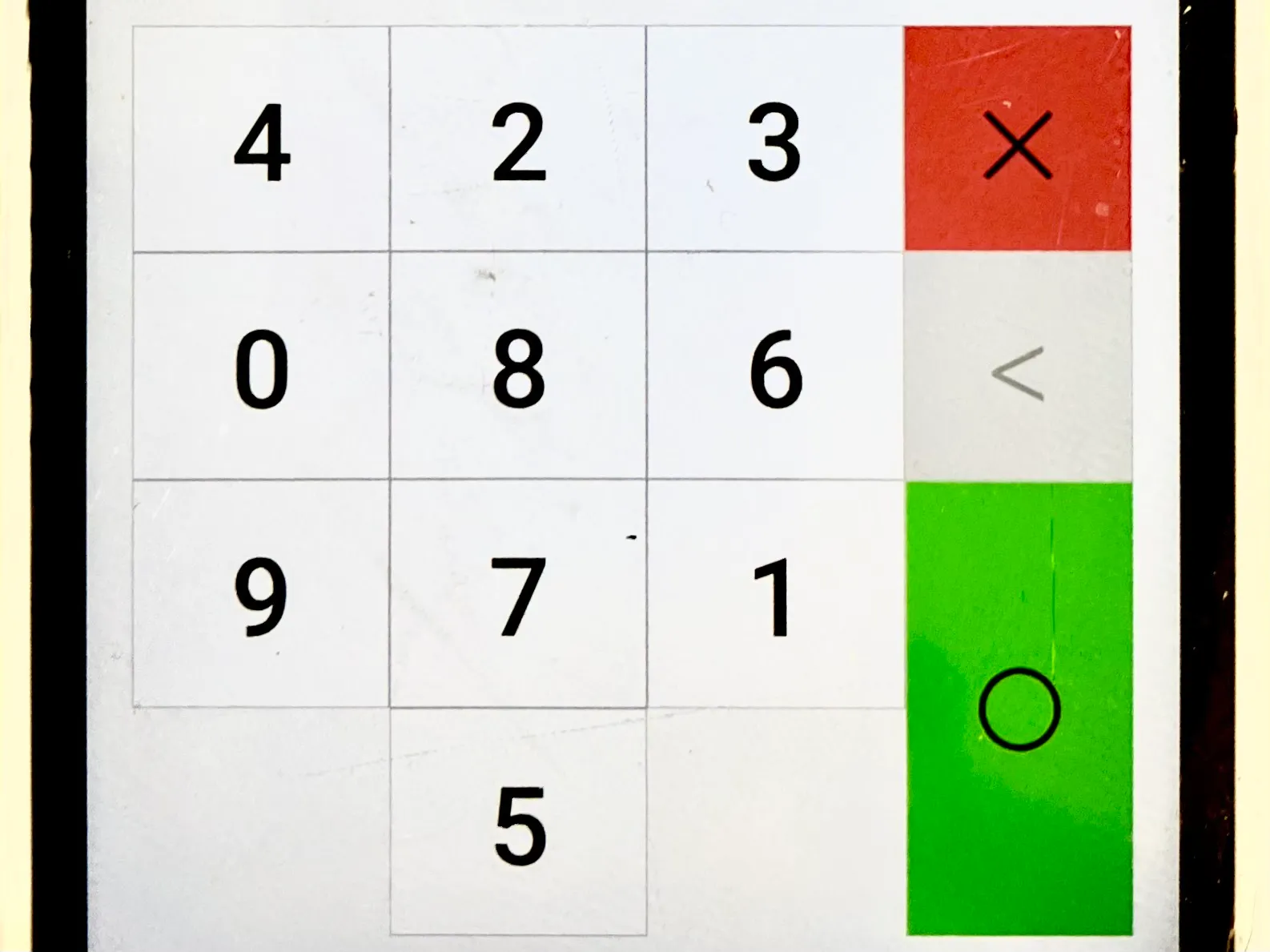

Credit card terminals in Japan are pretty similar to those in Canada — you can use tap (タッチ) or insert your card and enter your PIN to authorize the transaction. But there’s one twist that confused me at first. If you need to enter your PIN on a touchscreen, the numbers on the number pad are displayed in a random order!

I have no idea if this is unique to Japan or if it’s just new to me, but it does seem like a helpful security feature to ensure that your PIN can’t be guessed later based on the fingerprint smudges on the screen.

-

When I stopped by the Nintendo store in Kyōto, I knew I needed to get an product with the company’s oldest mascot on it. No, I don’t mean Mario, Link, Donkey Kong, or even Mr. Game and Watch. I’m talking about… Napoleon Bonaparte?

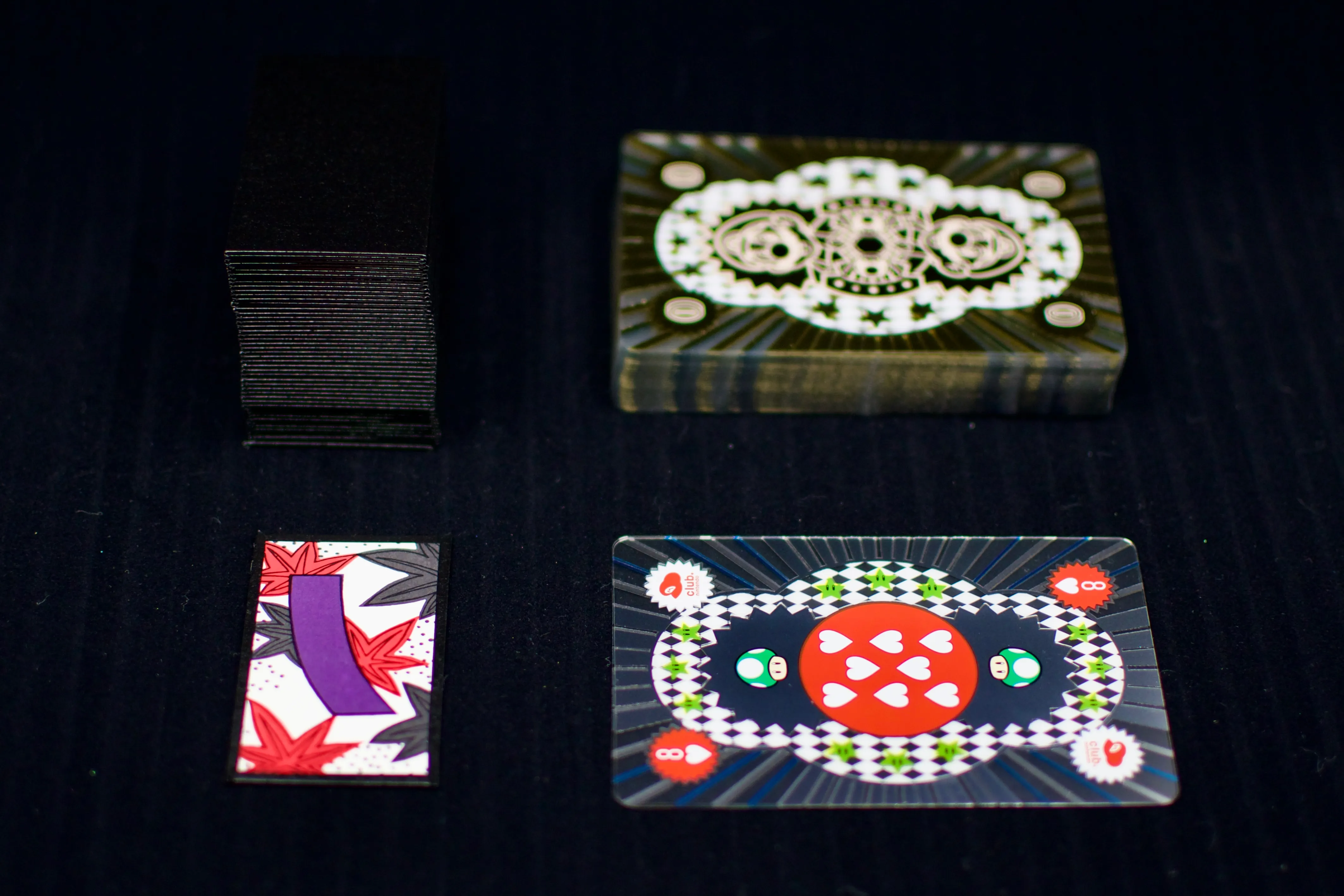

If you weren’t aware, the Nintendo corporation is much older than video games. It was originally founded in 1889 (Meiji 22) to produce hanafuda cards (花札) — which it still makes today!

A hanafuda deck consists of twelve suits of four cards each, all with abstract designs (originally to evade Edo-era anti-gambling laws). The cards are much thicker than western playing cards (トランプ) but are about a third of the size.

As shown above, Nintendo’s hanafuda come in a box with Napoleon’s portrait on it. That has been the case since at least 1901 (Meiji 34), although the company once had many other brands of cards featuring other historical figures like Saigō Takamori (西鄕 隆盛) and fanciful designs like tengu (天狗).

A rare poster listing all of Nintendo’s onetime 1 card brands (Yamazaki Isao/Tofugu)

It’s not clear why Napoleon was chosen, why he got top billing, or why he remains the face of hanafuda today. One theory suggests it was copied or acquired from an American brand, which in turn may have been named after an English card game, but this is purely conjecture.

-

Tofugu claims this poster to be from 1890, but I think something must have been lost in translation. The poster can’t be from before 1902, when Nintendo started making western playing cards.

-

-

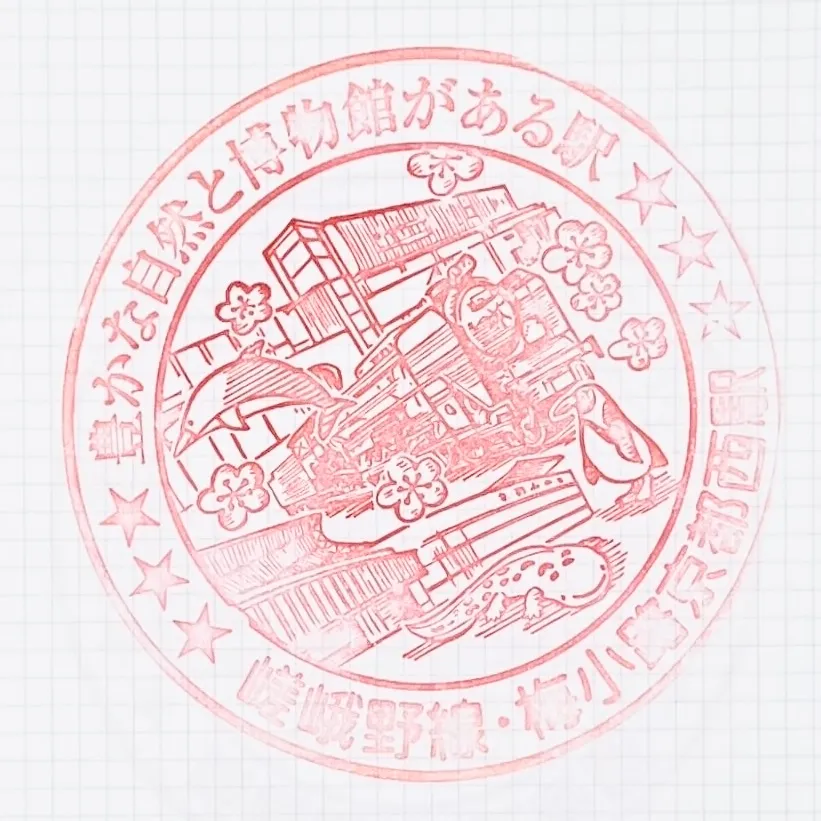

While in Japan, I dabbled in the perfect hobby for obsessive-compulsive travellers like myself: stamp collecting!

All over the country, train stations have distinctive rubber stamps (駅スタンプ) for travellers to mark their stampbooks with to commemorate their journey. These really took off in the 1970s1 when Japanese National Railways installed stamps at 1400 stations as part of its DISCOVER JAPAN campaign.

Prior to then, stamps were already offered at a handful of individual stations; enthusiasts had been collecting commemorative postmarks since the late Meiji era (1900s-1910s). An even earlier tradition had temples and shrines award stamps called goshuin (御朱印) as a proof of pilgrimage for their devotees.

With that said, here are the stamps I collected on our recent trip!

JR West stamps

I collected four classic stamps from JR West’s stations in Kanazawa and Kyōto.

The stamp for Kanazawa Station (金沢駅) features the rope-supported trees and stone lantern of Kenrokuen (兼六園).

The stamp for Nijō Station depicts nearby Nijō Castle, although I was just there for a transfer and didn’t go see it. (Photo: Eric Miraglia/BY-NC-SA)

The stamp for Umekōji-Kyōtonishi Station (梅小路京都西駅) combines elements from the Kyōto Aquarium (which I didn’t visit) and the Kyōto Railway Museum (which I definitely did).

The stamp for Kyōto Station (京都駅) has very faint ink from repeated use, but I’m pretty sure it shows the station building, Kyōto Tower (京都タワー), and the Yasaka Pagoda (八坂の塔).

JR East stamps

I absolutely love JR East’s refreshed 2020 stamp designs for its Tōkyō stations. Each incorporates one character of the station’s name with some distinctive feature of the surrounding neighbourhood. I collected six stamps from the Yamanote line (山手線) and one from the Chūō line (中央本線).

The stamp for Tōkyō Station (東京駅) uses the character 東 and depicts the station’s architecture.

The stamp of Kanda Station (神田駅) uses the character 神 and pays tribute to the biannual Kanda Matsuri. (Photo: 江戸村のとくぞう/CC-BY-SA)

The stamp for Akihabara Station (秋葉原駅) takes some liberties with the character 葉 and is designed like a circuit board in honour of Akihabara Electric Town.

The stamp for Ueno Station (上野駅) uses the character 野 and features Ueno Zoo’s panda, a ubiquitous mascot of the neighbourhood.

The stamp for Ikebukuro Station (池袋駅) uses the character 池 and a neighbourhood pun: Ikebukuro rhymes with fukurō (梟), meaning “owl”.

The stamp for Yūrakuchō Station (有楽町駅) uses the character 楽 and celebrates the surrounding shopping district and movie theatres, including the Toho headquarters.

The stamp for Ochanomizu Station (御茶ノ水駅) uses the character 茶 and has a guitar representing the nearly fifty musical instrument stores within walking distance.

Tourist stamps (記念スタンプ)

Train stations aren’t the only places you can get stamps. Tourist information centres at major destinations often have their own stamps for visitors, and even some stores participate in limited-time stamp rallies.

Nihonbashi (日本橋) is a famous bridge often depicted in art and home to Japan’s zero marker.

The Imperial Palace East National Garden (皇居東御苑), unlike the rest of the palace, is open to the public and has a stamp commemorating the date of your visit.

Yoyogi Park (代々木公園) is a quiet oasis in the middle of the big city. The pond and fountains depicted on its stamp were under maintenance when we visited.

If you’re counting, I collected three separate stamps related to Kenrokuen.

Kanazawa Castle (金沢城) is right across the street from Kenrokuen.

The Koupenchan (コウペンちゃん) store on Character Street had a stamp too!

Goshuin

Stamp collecting in Japan is at least informed by, if not directly descended from, the practice of receiving goshuin (御朱印) on a pilgrimage to a temple or shrine. Conversely, goshuin were influenced by the success of stamp collecting: many sects offer them to collectors and other travellers for a small donation, regardless of faith.

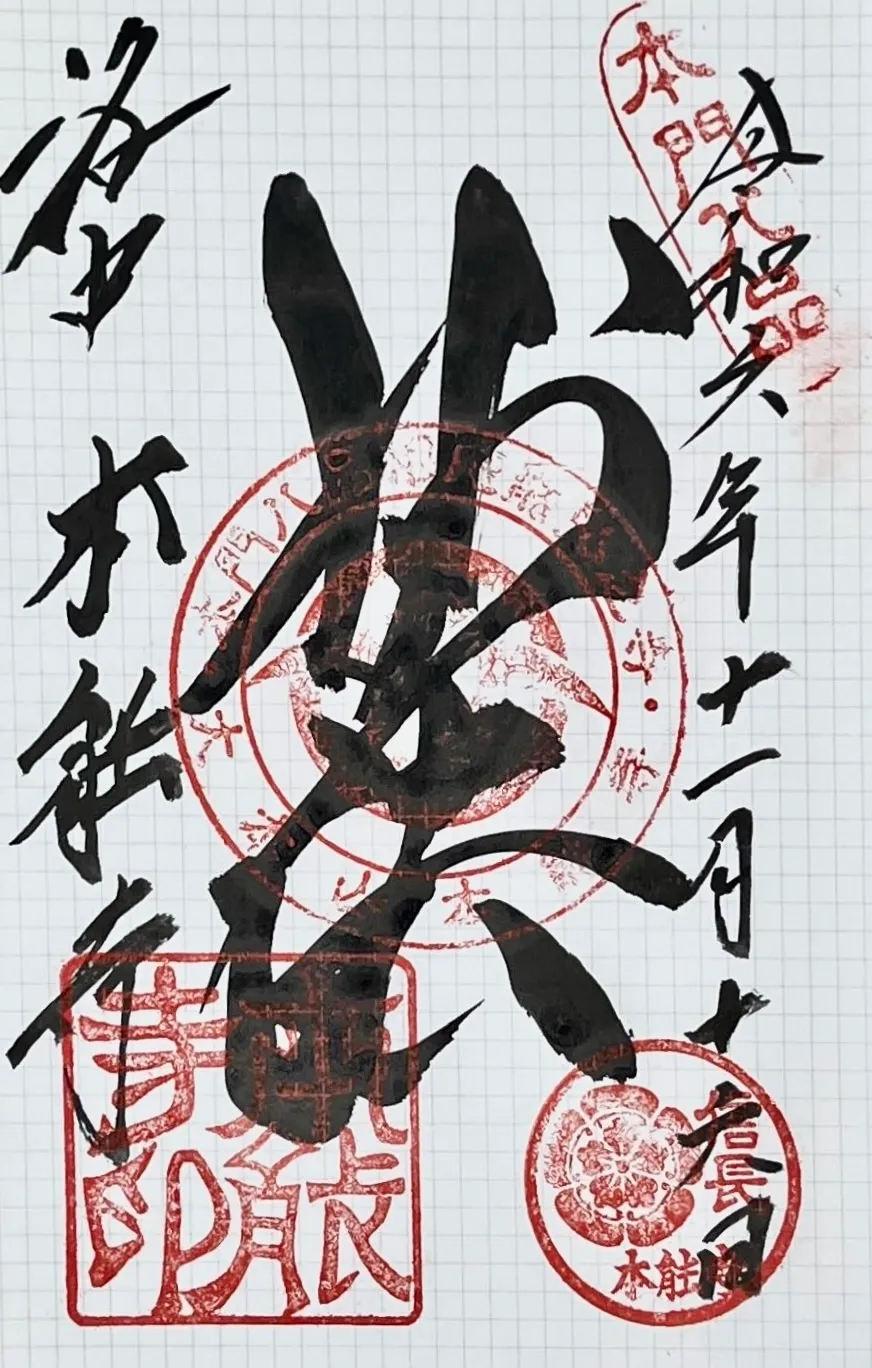

I had one goshuin entered into my stampbook at Honnōji (本能寺) in Kyōto.

The goshuin commemorating my visit to Honnōji on November 16 of the sixth year of Reiwa.

-

A Kyōto Railway Museum exhibit says the DISCOVER JAPAN stamps were installed in 1965, but I think it means the decade beginning in 1965 (the Shōwa 40s). Other sources confirm that DISCOVER JAPAN campaign kicked off in October 1970.

-

-

Leah and I are back from a three-week trip to Japan! It was my first trip to the country, and only my second time away from North America. Over the next few months, you can expect plenty of posts with photos, observations, and souvenirs from the trip.

For now, here’s an overview of our itinerary and some initial thoughts of how it went.

Tōkyō (東京)

Restaurants under the train tracks near Ginza.

We started the trip with four full days in Tōkyō. I was worried I’d be totally overwhelmed, but I was pleasantly surprised by how manageable it was. Part of that was location: our hotel in the centrally-located but less hectic neighbourhood around Ōtemachi (大手町) and Kanda (神田) provided a home base for us to retreat to.

But even the busiest areas of Shibuya (渋谷), Ginza (銀座), and Ikebukuro (池袋) were not as bad as I expected. It turns out that thousands of pedestrians and tens of vehicles is not much more of a sensory overload than an urban experience with hundreds of each.

We mostly stuck to the central core of Tōkyō within the Yamanote Line (JY 山手線) and took advantage of our central location on several metro lines:

- Marunouchi (Ⓜ 丸ノ内線)

- Ginza (Ⓖ 銀座線)

- Hanzōmon (Ⓩ 半蔵門線)

- Chiyoda (Ⓒ 千代田線)

- Tōzai (Ⓣ 東西線)

I’m very glad I studied the geography and metro lines of Tōkyō before I left!

Locations we visited in Tōkyō.

Kanazawa (金沢)

The wooden bridge to Higashi Chaya (東茶屋) and Utatsuyama (卯辰山).

After we had our fill of Tōkyō, we took the Hokuriku Shinkansen (北陸新幹線) to Kanazawa, the capital of Ishikawa Prefecture (石川県) on the coast of the Sea of Japan. The city is home to roughly half a million people and many traditional arts and crafts dating from the Edo era.

In our three days in Kanazawa, we stayed in the historic Higashiyama (東山) teahouse district and took a bunch of craft workshops I’ll cover in future posts.

Locations we visited in Kanazawa.

Kyōto (京都)

One of the many torii gates of Fushimi Inari-taisha (伏見稲荷大社).

The final leg of our trip was five days in Kyōto. The cultural capital is home to lots of historic landmarks and is ground zero for Japan’s challenges for overtourism. Our itinerary was focused more on Kyōto’s traditional crafts than the major tourist destinations, and it became even more so as we adjusted our plans to account for travel fatigue.

With hindsight, it would have been better to plan a slightly shorter trip and stay somewhere on the Karasuma subway line (烏丸線) rather than the tourist-heavy Gion district (祇園), but we still had a very nice time.

The highlight of Kyōto for me was definitely the railway museum — more on that in a future post.

Locations we visited in Kyōto.

Food

It is cliché to talk about all the amazing food one eats on a trip, but this has historically been challenging for me since I have a bit of a fragile stomach.1 Fortunately, Japan is full of food that is tasty and easy on the stomach, so our trip was both gastronomically and gastrointestinally satisfying!

Our favourite go-to meals were cold soba (そば) for Leah and unajū (鰻重) for me, although we also had excellent yakitori (焼き鳥), okonomiyaki (お好み焼き), oyakodon (親子丼), shrimp omurice (オムライス), and grilled salmon teishoku (鮭定食).2 I definitely missed my daily serving of peanut butter, but Japan’s famously incredible convenience stores (コンビニ) made up for it by providing snacks and reasonable emergency meals.

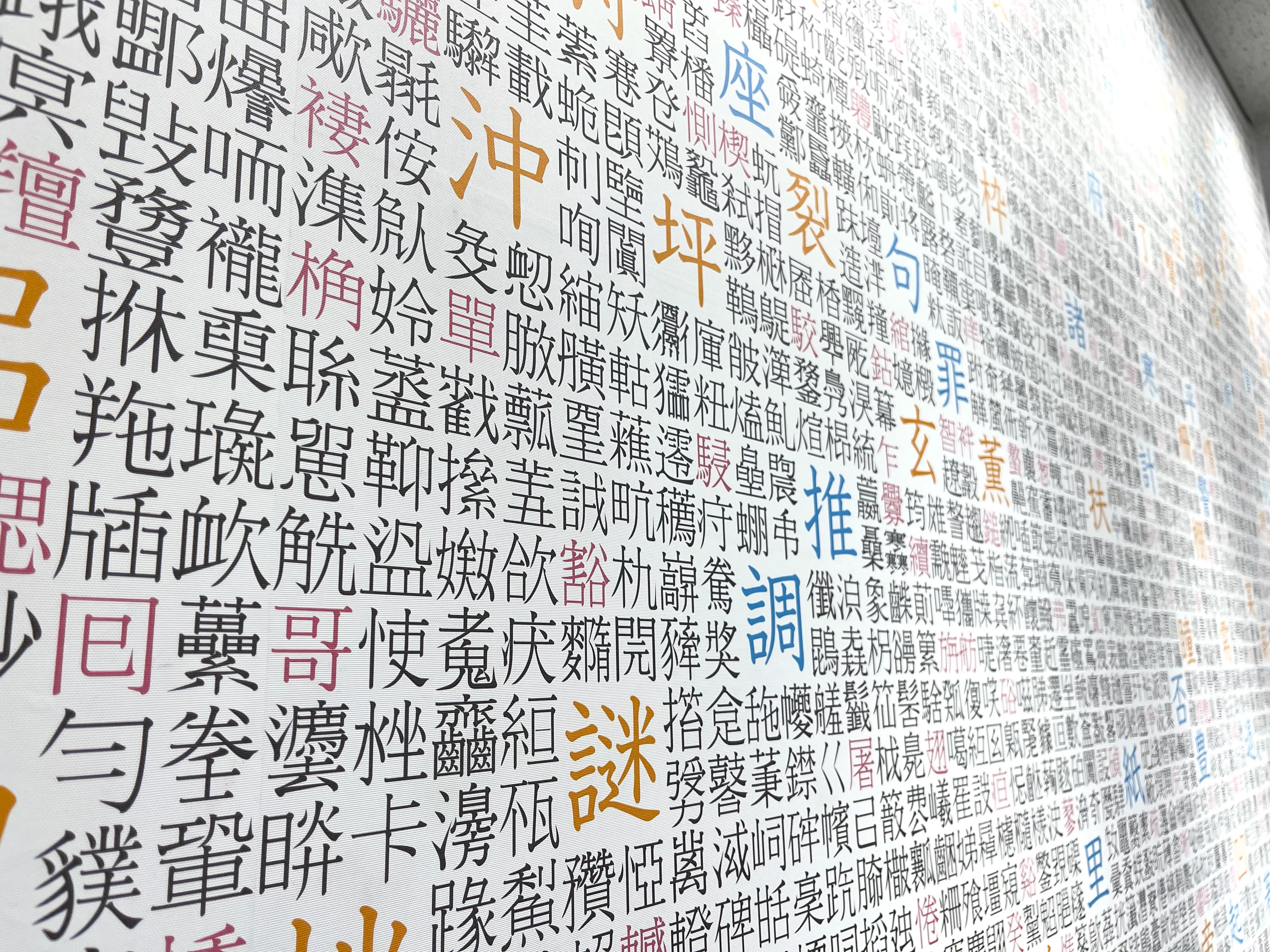

Language

A wall from the Japan Kanji Museum and Library.

It’s been a hot minute since I studied Japanese in university, but I was very thankful for my basic vocabulary and ability to read hiragana, katakana, and a handful of kanji. I’m sure it’s possible to visit Japan without knowing any of the language — million of tourists do it every month — but language was so core to our experience that I have a hard time imagining it.

Multilingual signage can be found everywhere at major attractions, in many restaurants, and on public transportation.3 But it’s a lot more efficient to be able to read and listen for directions in multiple languages, especially in smaller places where the English versions might be slightly dubious.4

I was surprised at how much value I got just from having a working knowledge of katakana. Japanese has a lot of English loanwords, to the point that you can navigate many stores just by sounding things out. At a drugstore, you might see my lips move as I read スキンクリーム as su-ki-n-ku-ri-i-mu — oh, this is skin cream!

People were universally very complimentary of our Japanese skills — not because we were any good, necessarily, but because we were showing consideration by putting in the effort. And they were more than willing to meet us halfway by simplifying their own speech, dropping in English words they knew, and being patient with us. There were a few very special interactions and experiences we were able to have in Japanese, and I’m very grateful to everyone we met for accommodating us.

Back home

We had a wonderful trip, but it’s great to be back home in our own bed with our cat and our routine. I’m sure we’ll be back one day, although it might take a few years to work up the energy for another trip of that length. Until then, I hope you’ll excuse me using this website to look back on my experiences for the next little while!

-

This goes double for Leah, who has Crohn’s.

-

Train stops are also helpfully numbered for those who have trouble remembering Japanese place names.

-

The worst were bus announcements in Kanazawa, whose English-language AI voice mangles the pronunciation of Japanese place names so badly that it’s useless for identifying your stop.

-

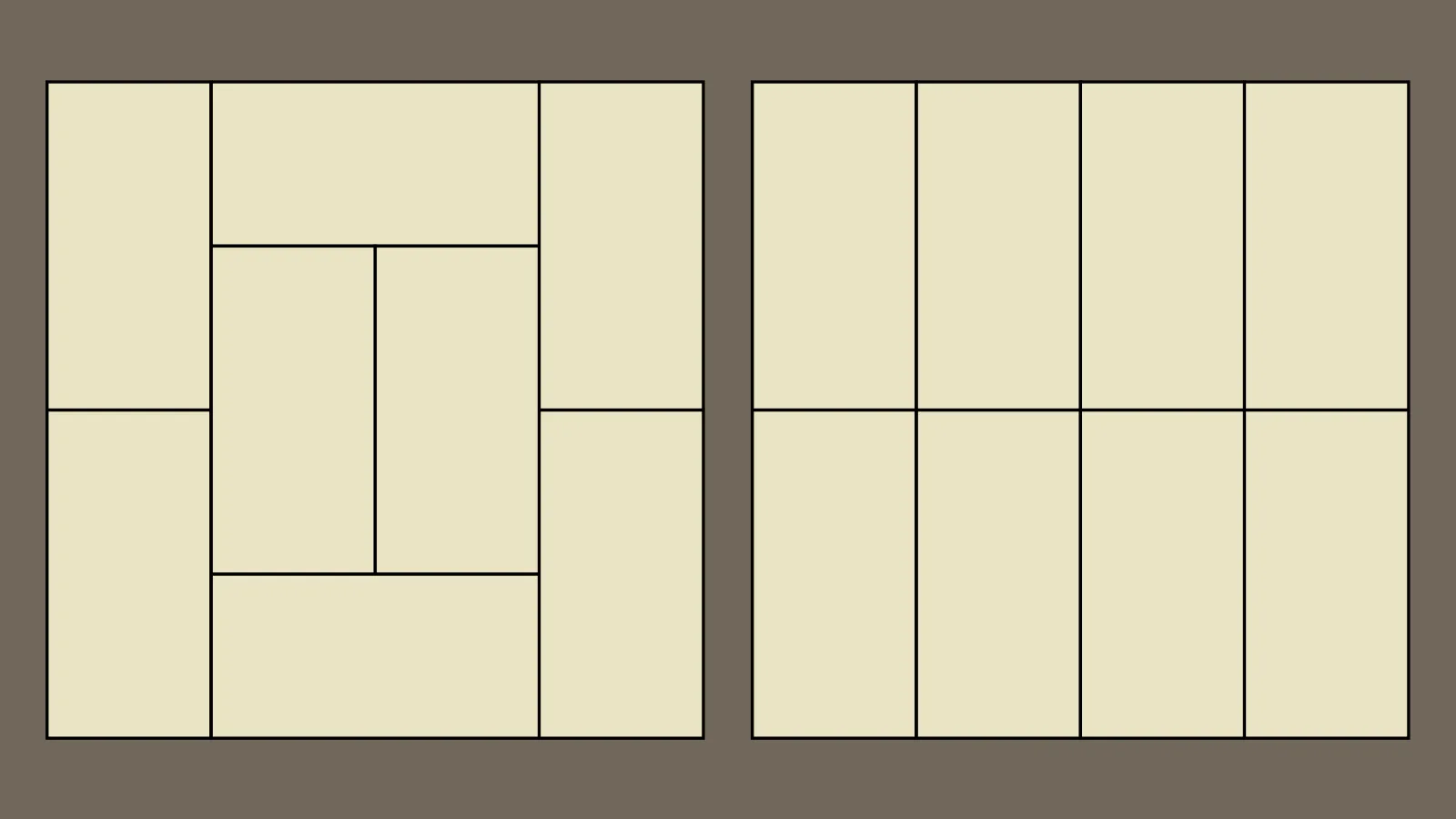

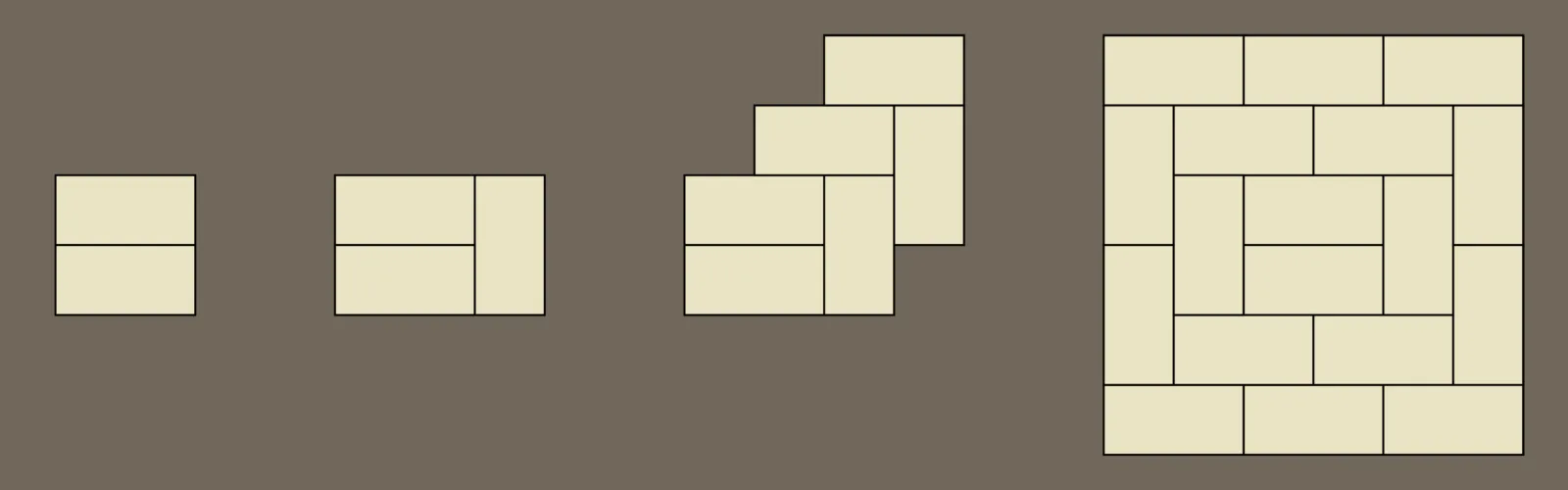

One of the most recognizable features of Japanese architecture is the matted flooring. The individual mats, called tatami, are made from rice straw and have a standard size and rectangular shape. Tatami flooring has been widespread in Japan since the 17th and 18th centuries, but it took three hundred years before mathematicians got their hands on it.

According to the traditional rules for arranging tatami, grid patterns called bushūgishiki (不祝儀敷き) are used only for funerals.1 In all other situations, tatami mats are arranged in shūgishiki (祝儀敷き), where no four mats meet at the same point. In other words, the junctions between mats are allowed to form ┬, ┤, ┴, and ├ shapes but not ┼ shapes.

Two traditional tatami layouts. The layout on the left follows the no-four-corners rule of shūgishiki. The grid layout on the right is a bushūgishiki, a “layout for sad occasions”.

Shūgishiki tatami arrangements were first considered as combinatorial objects by Kotani in 2001 and gained some attention after Knuth including them in The Art of Computer Programming.

Construction

Once you lay down the first couple tatami, you’ll find there aren’t many ways to extend them to a shūgishiki. For example, two side-by-side tatami force the position of all of the surrounding mats until you hit a wall.

Two side-by-side tatami force the arrangement of an entire square.

This observation can be used to decompose rectangular shūgishiki into

- blocks forced by vertical tatami,

- blocks forced by horizontal tatami, and

- strips of vertical tiles,

and to derive their generating function

Four-and-a-half tatami rooms can also be found in Japanese homes and tea houses, so naturally mathematicians have also looked into tatami tilings with half-tatami. Alejandro Erickson’s PhD thesis reviews and extends the research into this area. Alejandro has also published a book of puzzles about tatami layouts.

-

In reality, grid layouts are also used for practical reasons in inns, temples, and other large gathering halls.